News

Curios about the possibilities educational technologies offer

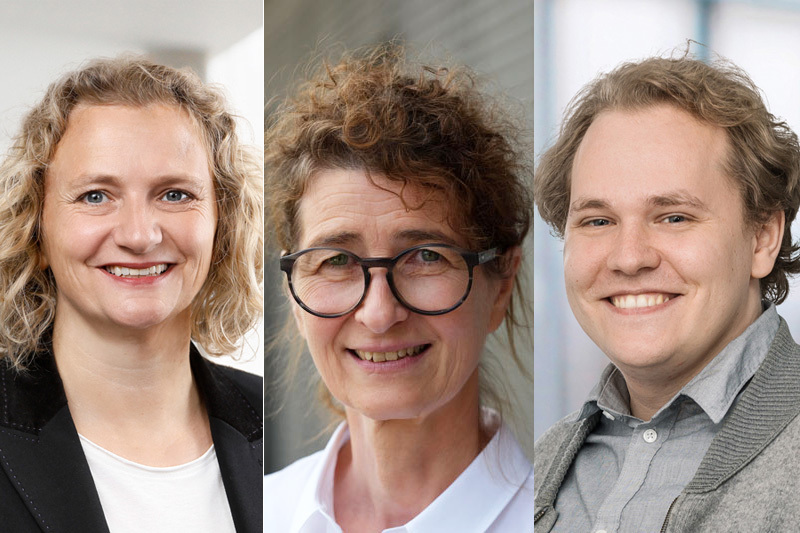

[04.12.2024]The AI.EDU Research Lab, with Claudia de Witt and her team, has been part of the CATALPA project from the very beginning. Since 2018, they have been researching how novel educational technologies can be used in a didactically meaningful way in higher education. An interview with Prof. Dr. Claudia de Witt, Silke Wrede and Lars van Rijn.

Photo: Henrik Schipper/Hardy Welsch

Photo: Henrik Schipper/Hardy Welsch

Sandra Kirschbaum: Let's start at the very beginning of AI.EDU. How did the original idea come about?

Claudia de Witt: Our fundamental driver has always been curiosity about what is possible with innovative educational technologies. We want to further develop the practice of higher education, make it more innovative, more conducive to learning. The AI.EDU Research Lab was launched at the Mobile Learning Day we organized in 2017. The topic of mobile learning was new at the time, and some of our ideas were ahead of their time. We got in touch with DFKI at the event – the start of our collaboration, which has been under the direction of Prof. Dr. Niels Pinkwart for some time now.

Our shared mission, which ultimately brought us together with DFKI, was even then: to provide all students with the best possible individual support on their way to a successful degree. At the very beginning, we had the vision of PIA, a Personal Intelligent Agent. An intelligent agent that supports students in their studies, for example in their motivation and self-regulation, but also strengthens their performance. At that time, however, we were still a long way from such a thing being possible.

Sandra Kirschbaum: That was the beginning of the AI.EDU Research Lab 1.0. You have now started phase 2.0. What was the focus then and what is it now?

Silke Wrede: The first phase of AI.EDU was initially concerned with the transfer and individual acquisition of subject-specific knowledge. The aim was to identify and design ways of personalizing learning and to experiment with the first “intelligent” applications. The focus in the second phase is now on research into the development of academic skills. Our project is closely linked to the dynamic developments in the use of AI in teaching and has actively accompanied and integrated them.

Sandra Kirschbaum: And what have been your key findings so far?

Silke Wrede: We have developed an educational recommender system that supports students in their learning process by providing recommendations. Results from the initial project period, such as the knowledge processing of a module in the form of an ontology, were initially used to link to relevant text passages in learning units. They now provide the basis for literature recommendations. At the AI.EDU Research Lab 2.0, we are currently working on combining recommender systems with large language models (LLMs) to support professional skills and scientific approaches to a problem, e.g. in the context of a term paper.

Recommender systems and Ontology

In our private lives, we are familiar with recommender systems in the form of product recommendations. In the field of education, they identify, for example, current levels of knowledge and take up the professional interests of students. They then offer support in the form of additional information, recommend possible next learning steps or provide suggestions for reflection.

Ontological theories deal with how to understand the (social) world, what it is and what to look out for in order to understand it better. In technical or computer science terms, the term also refers to a system of information with logical relationships.

Sandra Kirschbaum: What exactly does that look like in practice?

Lars van Rijn: In a module in which students are supposed to independently develop a term paper topic, for example, it would be like this:

We want to support students in defining their term paper topic. We examine this in an educational science module as an example. Our aim is to support students in acquiring skills, such as narrowing down a topic in the form of an academic question that also fits the module, or the ability to find relevant literature for it. So if, for example, a student comes to us with an idea or question for a term paper, the recommender system can establish links back to the module and say whether the topic is related to it, or it can provide additional literature recommendations. If we now incorporate the capabilities of LLMs, which not only recommend but can also explain excellently, we create additional added value. For example, an LLM can highlight why a source might be relevant.

Sandra Kirschbaum: And how do you arrive at insights here that help in teaching?

Silke Wrede: For example, I conducted a qualitative study on how students interact with generative AI tools. The students were given an assignment based on the module. The students' work on the assignment was then recorded using the thinking aloud method. This revealed a few challenges that students faced: As expected, students with little experience using ChatGPT or Elicit had difficulty formulating prompts. In addition, they found it difficult to adequately assess the capabilities and limitations of the tools. We also noticed that there was little diversity and creativity in the prompt generation. Rather, the students stuck very closely to the task at hand. For us, this is an indication that it takes room for experimentation and experience to learn how to use generative AI in a competent and constructive way. Quantitative follow-up studies are already underway.

Claudia de Witt: For us, these results show how important it is for research to focus on the extent to which technologies are useful for education and learning, and that we integrate educational technologies in such a way that they actually add value and help learners. We can't just use AI for the sake of the technology and expect it to work. Creating AI tools and applications with didactic value is a complex challenge that we will continue to tackle in the years to come. Data protection and ethical issues will always play a central role in this.

Sandra Kirschbaum: That's the perfect segue into a look into the future. If you could wish for what your work would mean in practice in the future, what would it be?

Foto: KI-generiertes Bild

Foto: KI-generiertes BildClaudia de Witt: Then there would be intelligent agents or learning guides for higher education that promote motivation and performance in a privacy-compliant manner – multifunctional and without media discontinuity. Basically, the ideal would still be the Startvision of AI.EDU – namely PIA. A complex, multimodal digital intelligence that not only masters a task, but also keeps an eye on deadlines, suggests support, and checks schedules when preparing for exams, but at the same time allows students self-determination and autonomy. It doesn't help if an AI takes over everything for me. It should support me in my development and not slow me down by taking away all difficulties in my development.

Silke Wrede: I would like to see a system that supports students based on their needs. Qualitative research has shown that students want to develop their subject interests and monitor their progress with the help of the generative AI. And that's exactly where I would like to start.

Lars van Rijn: My hope is that we will have technological support for superficial questions, freeing up resources to go into depth in teaching even more often than before. This leaves more time for the kind of teaching we all want to see – and we would be a big step closer to more intensive, personalized student support. Routine tasks, which are still the main focus for teachers and tie up a lot of resources, will then be taken over by AI assistants. Intensive content-related support often conflicted with these tasks. This is precisely what I would like to see, but in the future it should be resolved by AI support.